Group decision making is how teams get stuff done. We join forces in order to achieve our goals, creating groups, teams, and whole organizations in order to advance toward a vision. Making decisions on how to move forward is an important part of making this work, but when it comes to group decision making, the process can become messy or ineffective.

Why is it so common to argue over whether a group decision was taken or not? When should we decide together, and when is it ok for a group leader to go ahead with a final decision? What are the different ways of taking decisions? Which will work for you and your group members? In this article we’ll cover all you need to know, as a facilitator or team lead, to improve your group decision making.

In this piece, you will find out what you and your team need to know to take a crucial meta-decision: deciding how to decide!

You’ll read about different types of decision-making rules, when you might want to use each, and how to prevent common sources of misunderstanding during group decision making. You’ll also find plenty of practical tips, such as giving decisions a time limit, tips for prioritizing with dot-voting, and how to enshrine decisions in the meeting minutes.

What is group decision-making?

Group decision-making is the act of collectively making a decision as a group, often using voting techniques and discussions to arrive at a consensus or majority.

While a group leader may still make a final decision in some scenarios, group decision making is defined by the fact that everyone in a group has some say in choosing from the option or solutions on the table. A group decision can be as simple as voting on where to hold your next team retreat, or it can be as complex as choosing the future vision for your product or company.

A group decision making process typically guides group members from first ideating on and critically reviewing possible solutions, all the way through to making a final choice. Whats crucial is that

What are the advantages of group decision making?

Choosing among different paths forward is hard enough when we are on our own, and it sounds pretty complicated to do it in a group. Done badly, collective decision-making can be frustrating, take more time, be a source of conflict, and ultimately lead to bad decisions! So, why decide together in the first place? What are the advantages to group decision making?

There are, ultimately, two main advantages to running a group decision making process:

- Quality: Diversity of opinions can lead to more sustainable and more innovative solutions; risks can be spotted earlier when more pairs of eyes are scanning the horizon.

- Buy-in: When people take part in choosing a course of action, they are more likely to contribute to its implementation.

The quality of a decision made collectively is often better than that made by an individual. During ideation, you often have as many ideas as there are contributors, and when a group discusses possible solutions, they’ll help ensure all bases are covered. Diverse groups are also better positioned to consider creative ideas and other group members may see the blind spots a group leader may have.

This second point, buy-in, is often the main driver for opting for participatory, inclusive decision making rules. It’s especially important to include those people who are explicitly involved in implementing the results of a decision.

In the next paragraphs, we will look into how choosing a decision making process determines the level of engagement and participation.

What are the disadvantages of group decision making?

Conversely, there are two main risks associated with group decision making which are worthy to consider. Any group is subject to internal dynamics, and while none of these are blockers to making a decision as a team, it’s imperative you consider these ahead of bringing people together to make a decision.

- Groupthink, meaning a situation in which the group chooses harmony over effectiveness. This leads to picking ideas that are low-risk, but also not innovative. The group will tend to coast along; enterprising minds and personal accountability are discouraged.

- Timing and efficacy: achieving both effectiveness and inclusion is tricky. Inclusion and participation, especially at first, take a lot of time. In an emergency, a fast decision may be required.

Good facilitation practices are instrumental in avoiding those pitfalls. Mitigate the risk of groupthink by creating an environment of trust, giving space for individual reflection and ideation before sharing, and encouraging “black hat thinking”.

This term, a nod to DeBono’s Six Thinking Hats methodology, refers to having dedicated moments in which to look only at the risks and dangers of choosing a certain path.

As for the second pitfall—taking too long to decide or being ineffective—-this can be true at the start of your journey in collective decision making, but the time it takes will decrease with training, practice and the use of the right group decision making process.

When group confidence is low, or you approach group decision making in a haphazard fashion, it can be hard to reach the point where each group member feels able to make a decision.

The advice in the post is a great way to improve how your group decides together, though you’ll also find this list of group decision making techniques useful if you’re looking for a complete process and framework for collaborative decision making.

Also, a team can become skilled at choosing when to take group decisions, e.g. for overarching policies, and when to leave things up to individual decision making, e.g. in everyday operations. There is absolutely a balance to be found between using decision making when working on complex tasks and also finding a way to enable individual autonomy and avoid additional overhead.

Discussing when it’s a good idea to decide together, and when to leave use individual decision making or small delegation, is a great start for a team conversation. Raising the group’s awareness around the topic of decision making is the first step toward improved decisions.

As a general rule of thumb, consider the size and impact of any decision before bringing it to all the members of your group. Involving group members in a decision about what you are having for your lunch isn’t the same as discussing what to order for the whole team!

How to choose a decision making process

How are decisions made in your organization? In most cases, groups rely on a combination of hierarchy (the person in power decides) and informality (someone decides but we don’t know how we got there). Sometimes this works, but a lack of clarity around how we decide can easily lead to resentment, and to faulty implementation.

The more hierarchical the structure, the less information will flow to the top, leading to potentially damaging decisions. Furthermore, a decision taken top-down is harder to implement, as people might not understand it, might disagree, or the decision might make it harder for them to do their jobs.

In full informality, which is what happens when a group of friends gets together to choose where to have dinner, there is a high risk of creating misunderstandings and conflicts. Who got to choose, and why? Is there a gluten-free option, and if not… well why didn’t you say that your cousin cannot eat pizza?

Awareness is key. The single best advice we can give about creating a decision making process is this: have a conversation around it. Clarify who is deciding what, when. Find out if this works for everyone, or if improvements need to be made. Share a vocabulary of decision-making: is this a consultation? Or is it a collective decision (aka deliberation)? Are we using consent?

In time, by getting familiar with the nuts and bolts of deciding, your team will become nimble at choosing how much decision-making responsibility should be shared and how much is a matter of personal accountability.

Topics you might want to cover when creating a group decision making process with your team include:

- How are decisions taken in our group?

- Is this working well for us? Do we need to change anything?

- What decisions do we take together and what is up to individuals?

- What happens if a decision is not implemented?

- How will I know what was decided (including if I missed the meeting)?

In this article, we have collected some training activities that can help make teams learn more about decision-making while having some fun in the process. Delegation levels, for example, is a training and discussion activity aiming to help a team clarify how much management should get involved in a decision, and when team members have the authority to act on their own.

What decision-making processes can you use?

A healthy culture of decision-making begins with awareness of the different possible ways to take decisions. In short: deciding how to decide! Effective group decision making is built on a shared understand of the process you’ll be using.

In this section, we will look at different possibilities for decision-making processes and rules: when to use them, what the consequences of that choice are in terms of participation and engagement, and what to look out for. It’s a great starting point for improving group decision making in your organization!

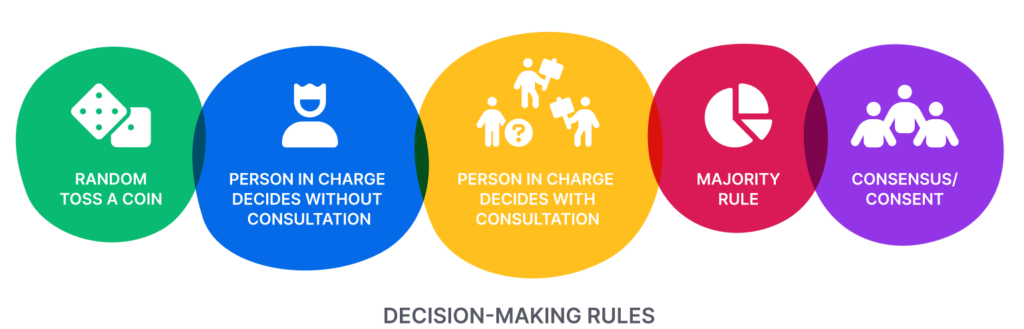

How many ways of making decisions do you know? When I ask this question in trainings on group dynamics, participants are generally quick to point out at least these two: person-in-charge decides without consultation (“dictatorship!” say my students of peace studies), and majority vote.

For an individual or a majority to decide are the main decision-making rules in the current political landscape, so they easily come to mind. Some digging leads to at least one other: a person-in-charge deciding with consultation. This is a common experience in many workplaces: your boss might ask for advice, but ultimately the choice, and the responsibility, falls with her.

The last two decision-making rules sit at opposite ends of a spectrum in terms of how much effort they require, and how much participation they elicit. A spectrum that runs from randomized methods of group decision making all the way to consent rounds.

In the next paragraphs, we’ll go through each one of these group decision making processes and learn more about what they mean, and imply, for facilitating group decisions.

Person-in-charge deciding with consultation

In a consultation, a group is convened to provide support and advice to a person with whom the decision ultimately lies. One interesting point to note is that if the decision making rule is clear, there is no need for the group to reach a final agreement and converge. The group decision making process stops before that, and the decision maker or group leader can take divergent opinions home to mull upon and select later.

The only real risk with this decision-making rule is that participants may cater to that one person exclusively, as he is the only one they need to convince: it will be harder to get the group to listen to one another. Participants may hide their own ideas just to please the boss. Good facilitation practices, particularly those that revolve around getting ideas in writing before sharing them and explicitly calling for ideas from other group members, can mitigate this risk, by building an environment of mutual trust in which contrary opinions are welcomed and not immediately shot down.

Person-in-charge deciding without consultation

A person-in-charge deciding without consultation may not be very inclusive, but it can be exactly what is needed in an emergency situation. You probably don’t want the fire brigade to sit down in a circle for an in-depth consultation before taking action! And even outside of emergency scenarios, if the person is an expert in their domain, and the problem is not overly complex (say, your doctor prescribing an antibiotic) this may well be the most appropriate rule.

Trouble brews at the horizon, though, when the town mayor organizes a meeting to discuss the new neighborhood traffic plan with citizens, except that all decisions have already been set in stone. The only possible role left for the attendees are those of passive listeners (or possibly protesters). In fact, a tendency to confuse meetings called for sharing information and for asking for advice has led to a lot of disappointment and mistrust in public participation projects.

There is a tight connection between types of decision making rules and levels of engagement. In some group decision making processes (randomization and deciding without consultation), active engagement is discouraged.

Using these processes can be valid based on the decision that needs to be made, but be certain to let every group member know what to expect before joining such a decision making meeting.

Majority vote

In majority voting, in its many variations (50% +1, pondered majority, and so on) the group simply takes a vote, and the decision approved by the majority wins.

“All in favor, raise your hands” is the default way of group decision making in many settings, at least in Western culture. It is of course the way democratic countries run elections. It’s fast, it’s efficient, and it is easy to understand.

On the other hand, majority voting creates by its very nature an issue with representation of the minority. It is ok to just gloss over their interests? Maybe their point is valid, something the organization should listen to. In all likelihood, if their objections are not, at the very least, heard, they will stand in the way of the decisions’ implementation.

Still, majority vote is familiar, scalable, and functional for large numbers of people. In the words of Sam Kaner’s classic Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making, “When expedience is more important than quality, majority vote strikes a useful balance between a lengthy discussion […] and the lack of deliberation that is the danger of the other extreme.”

At the other end of the spectrum, for very important policy decisions, we find consensus and consent-based decision-making. Similar but different, these are sibling processes for seeking full agreement within a group.

Consensus

Formal structures designed to reach consensus emerged in facilitation in the 1970s, in connection with direct action and nonviolent protest movements, particularly in the US. Today, they still enjoy a lot of favor in egalitarian groups such as many eco-villages, intentional communities, and cooperatives.

The basic idea behind consensus is to seek full alignment and participation in the group, but to do it formally, step-by-step, in order to avoid the risk of groupthink or the effect of secret power plays.

When seeking consensus we seek for a decision “that everyone agrees with”. Agreed-upon hand signs or color codes (green for “full agreement”, red for a “block”) can be used to test the group. If any one person blocks the decision, it’s exactly that: blocked. At that point, the proposal needs to be re-shaped to integrate that person’s objection. As such, any final decision is a reflection of the opinions of every group member – this takes time and more group discussion than other processes.

With respect to majority voting, consensus requires a lot more training, and discipline. Its advantages lie in building trust among members of a group, and ensuring participation and enthusiasm for implementing a decision. The power that a single individual has to block a whole group can be mitigated by adaptations, such as “voting to vote” (when a group that is consensus-based can decide to switch methods and vote) or “consensus minus one”.

Consent

In consent-based decision making we are not looking for “everyone agrees” but, rather for “nobody disagrees”. You may well be thinking: “But, wait, isn’t it the same thing?” Almost, but not really. To begin with, there is something to be said about the difference it makes in the human psyche to be looking for the “perfect, ideal, best solution for all” (which is where consensus tends to lead) and to be looking for a “good enough for now, safe enough to try” decision, as is the motto of sociocracy, a form of governance that is founded upon consent.

Sociocratisch Centrum co-founder Reijmer has summarized the difference as follows: “By consensus, I must convince you that I’m right; by consent, you ask whether you can live with the decision“. The organization Sociocracy for All has manuals and materials to learn more about this form of governance, which was ideated by Gerard Endelburg in the 1970s.

While one should be aware that there is a lot more to Sociocratic organizations than the use of consent, I have found that knowing about the process for consent is immensely helpful to my day-to-day facilitation practice.

Proposals are written somewhere visible before opening the discussion. Next, the facilitator invites a round of clarification questions: do we fully understand the proposal? Many potential misunderstandings and conflicts are avoided by this simple action. Later come rounds of what are called “quick reactions” which is a space to test how the proposal feels to people.

A whole process is therefore followed before even testing for consent. And, furthermore, objections must be grounded in pragmatism and connected to the group’s purpose. This is not about looking for the best possible idea that everyone loves, but about looking for the plausible next step that everyone can live with.

Consent decision-making has many interesting aspects and tweaks that aim to satisfy effectiveness and equivalence at the same time. Despite requiring training and discipline (as well as knowledgeable facilitators!), consent is a phenomenal way of deciding together, especially in policy choices that will benefit from full involvement and engagement of everyone.

In this template you can find a suggested flow of how to go from an initial brainstorming of solutions all the way to consent. Let us know if it works for you! If you have other experiences using Sociocracy and consent decision making, please share them in the comments, or in our Community!

Randomization

Using a randomized method for decisions might seem a bit daft, but it’s a great time-saver if the decision is inconsequential. This might mean picking a name from a hat to set up “secret Santa” matches for a Christmas office game, or throwing a coin to decide if the workshop break is going to be 15 or 20 minutes (something I do all the time).

The consequence of using the group decision making technique and letting Lady Luck do the work for you is that people will not be engaged in discussion around the decision. For unimportant decisions, consider picking randomization over deciding yourself, as it’s perceived as more just and fair. As an added bonus, randomized decision-making can be fun and can take the stress out of group decision making.

How to your decision-making process explicit?

By sharing knowledge about different types of decision rules, and their pros and cons, you are building capacity within an organization. Once you know the options on the menu, it’s a matter of sharing, on a case-by-case basis, what kind of decision you are asking people to take today and what group decision making process you will be using? What rules will you be following and who will be included?

By taking that “meta-decision” (how will we decide?) the ground is cleared for clarity and mutual understanding of what is expected from participants in a decision making process.

Different decision making rules lead to different levels of participation. If I know a decision will be taken by the person in charge, they are the ones I am trying to convince. If I know there will be a majority vote, I’ll be aiming to persuade the highest possible number of my peers. If we are working on consent, my attention will go to how aligned my proposal is with the organization’s mission and values. If the decision is random, I’ll relax in my seat and let it go.

The same organization or team is likely to need different types of decisions at different times. Base your choice on the level of importance of the decision, timing considerations and desired levels of engagement.

Getting to convergence: decision making as part of a longer process

The act of taking a decision is only one step in a longer decision making process. That process begins once a problem is stated, and its scope defined (“What do we need to solve?”). And it ends (if ever) once a decision is evaluated and looked back at in retrospect.

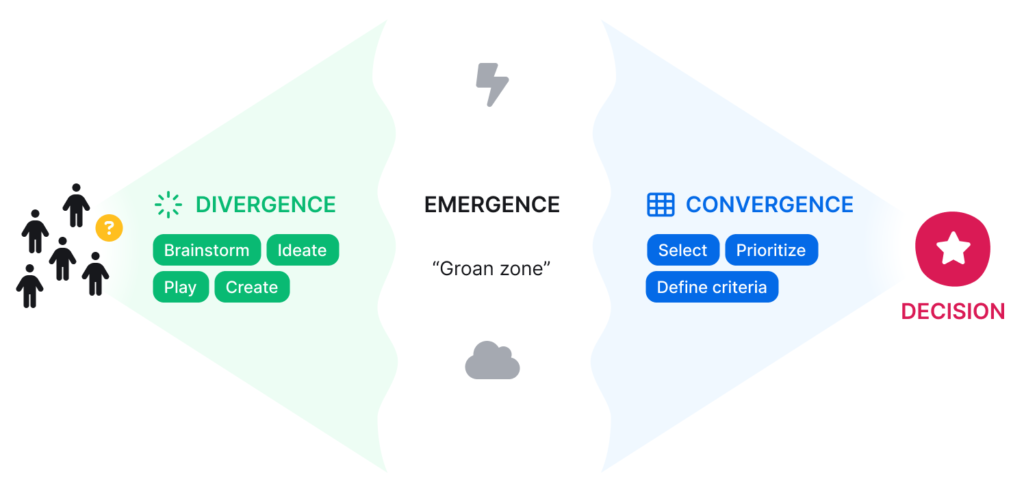

Before a decision is made, there must be enough time and space given to exploring options and finding alternatives. In the classic “diamond” of facilitation, codified by Sam Kaner in the Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision Making, this phase is called divergence.

Divergence is the time for brainstorming, creativity and play. It’s when we want to hear all ideas, no matter how improbable. Some teams thrive in divergence and could spend endless hours ideating. But there does come a point when participants have had enough of this stage, and it’s time to move on to what is called convergence.

Convergence is the space for categorizing, prioritizing, taking resource allocation into account, being realistic about choices. In between there is the space for emergence, which is when, through a combination of ideas and, often, constructive clashes, something new “emerges”, a solution that was not available in the room before the meeting began.

Each of these phases—divergence, emergence and convergence—requires attention, time, and different types of processes to accompany them. We can pick a brainstorming technique to support divergence, for example. Allowing people to move around different tables and topics of conversation makes emergence of new solutions more likely.

Using matrixes and/or prioritization tools, such as dot voting, are great ways to lead a group towards convergence. And once there is a sense of being almost at an agreement, that is, once the convergence phase feels complete, it’s time to move to actual decision making.

Getting to convergence with dot voting

The movement from ideation to decisions is facilitated by activities and tools that help prioritize, categorize, and take into account limiting factors such as the availability of time and resources. Here you can find a list of methods from SessionLab’s library that help with guiding a group towards convergence.

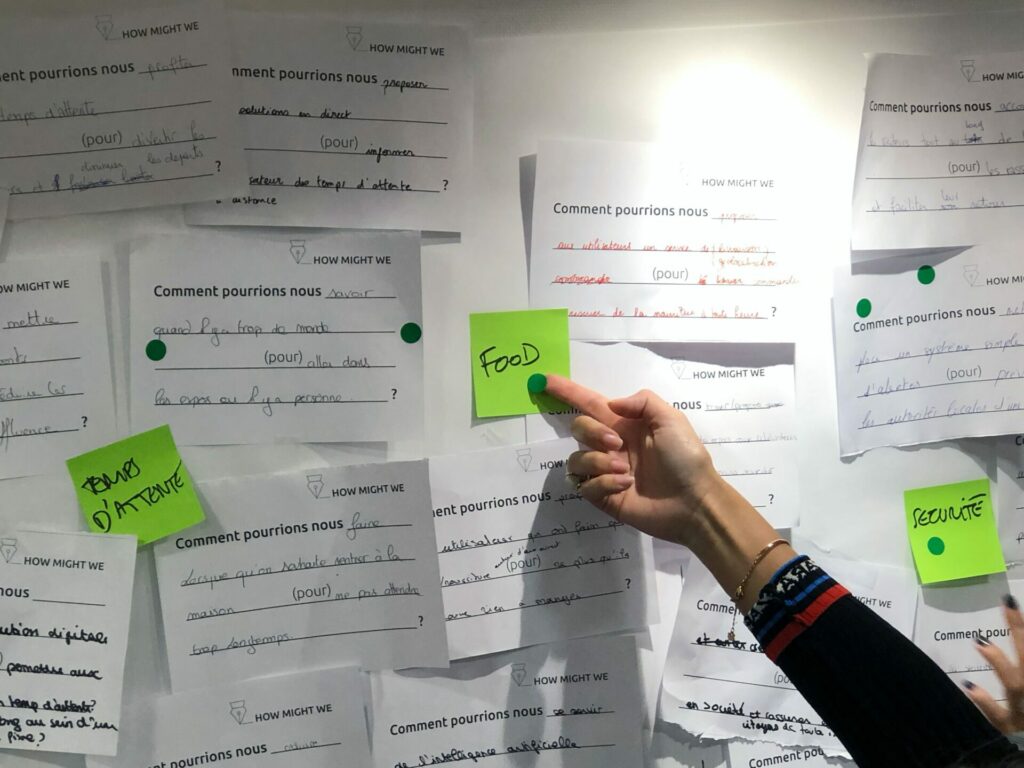

Many facilitated decision-making processes go something like this: first we brainstorm options, next we vote on them, and then we choose one or more to continue working on and refining. This sequence can apply, for example, to a consultation process, in which a team lead might ask the group for recommendations on actions to take in the next few months. There does not necessarily need to be “one single answer”, but an indication of interest.

What we are looking for is not yet a decision, but a prioritization. And for prioritization, nothing beats dot-voting! Whether you prefer sheets of sticky dots or just giving people markers, whether you are working in the physical world or with votes online, dot-voting allows a group to clearly and quickly visualize preferences and priorities at a glance.

When inviting group members to prioritize, it’s important to pay attention to the words you use in formulating a question. Rather than using generic terms such as “vote for your favorite” or “put three dots on the idea you think is best”, take some time to consider what kind of direction you are really looking for.

An inspiring version of this comes from John Croft, who suggests asking “Which of these actions, if taken first, will lead to all the others happening?”. That gives a clear sense of looking for priority in time, and speaks to unblocking resources and enabling future actions. Asking “what should we do first?” and asking “which of these actions are most important?” will inevitably yield different results, so this is a question worth carefully pondering!

Here are some things to keep in mind when running a dot-voting activity:

- Give participants some quiet time to carefully read the options and think about them individually before beginning to vote;

- Set some basic rules, such as “don’t give all your votes to the same option”;

- It can make a lot of sense to assign more votes to managers/team leads than other group members, just state this clearly at the start;

- Align around criteria: what are we voting for? Are we looking for “our favorite” idea or “the most feasible”?

Dot voting is not the only way to rank options, of course! You can facilitate the shift from divergence to convergence by introducing matrixes and other tools that help prioritize, categorize, and take into account limiting factors such as the availability of time and resources.

Mark clearly when a decision has been taken – Is this now decided?

Viki, one of four graduate students working on a team assignment together, pulled me, their team coach, aside. “Yesterday we had finally decided to go in this direction with the project, but now those two are talking about this other thing!”. Angry at her teammates, and utterly confused, Viki wanted me to step in and stop the rest of the group from continuing to brainstorm new topics. A half-hour or so later, I casually sauntered over to their table: “Hey people, what is going on here?”

Hans and Kristin were excited to bring me up to speed on all the new ideas and directions they are going in. Vittoria just rolled her eyes and glanced over to me in desperation. “Ok” I asked “So it looks like you are coming up with lots of great ideas, is that it?” “Yes! And we are loving this process!” Hans was practically jumping up and down in excitement. “So, just to check… have you decided which direction you want to go in?” “Not yet” from Hans came right at the same time as “Yes, we did!” from Viki.

The situation in which part of the group is convinced a decision has been made, so now it’s time to act on it, while another part of the group is sure of the opposite, is a very common one. It’s also a popular source of conflict. Both parties are generally in good faith: this misunderstanding over whether we have decided or not can lead to terrible rifts, as the two begin drifting away from one another in their actions, and pointing fingers.

The solution, as Viki’s group quickly figured out after a moment of debriefing and clarification with their coach, is very simple: make this step a part of your group decision making process and mark clearly when a decision has been taken!

How to define when a group decision is made

Every group will find its own way to defining when a decision is open and when it’s been made. The most important piece of advice is common sense: write down decisions in the minutes and clearly state what they are.

Create a bright yellow text box at the very top of the minutes’ template, with each decision written down, roles assigned to its execution, and a deadline for implementation and/or to check on the decision.

Beside this, a group can add little rituals: a round of applause, a group cheer, writing the decision on a special whiteboard. Asking: “Does everyone agree?” and in silence, moving on, will not work. Ask for a specific sign of commitment, or you will never know what that silence actually meant.

Give decisions a time limit – When will we check on this decision?

Ending the decision-making process can be frustrating for people with more divergent mindsets, who would like to go on ideating forever. Some team members might, therefore, consciously or not, try to keep the conversation open, possibly from a fear of stifling creativity. Putting a time limit to decisions helps assuage that fear: this is decided for now, but not forever.

Every decision should have a term assigned to it: “this policy will last for one year, then we will reconvene to check on it”. This also means we are ok with decisions being imperfect, as we learn from experiments and failed policies.

Naturally, in order to check whether a decision was effective or not, it needs to come with a set of metrics or targets for evaluation. Metrics can be as rigorous as Key Performance Indicators or more flexible, like Objectives and Key Results, depending on the kind of organization you are working with.

Last but not least, someone needs to be assigned to making sure the decision is implemented and actions are taken. Add names and/or roles to the decision in the minutes!

How to check on a group decision

Reconvening at the end of a decision’s term to check on it is instrumental to a learning organization. Was your final decision the right one? Was every group member happy with the process?

At the end of the term, reconvene the team to take a look back at what worked well and what needs to change. This is key to enabling learning and team growth. Reflections might lead to changing ways you take decisions together, maybe even coming up with a bespoke method adapted to your own team.

Here as SessionLab we use the online tool Team Retro at the end of every project, collecting insights asynchronously then holding a meeting to discuss key points. One of the things we’ve learnt is to spend time in the “What worked well” space to celebrate our wins and build on our strengths.

Here are some key points for discussion you can base your retrospective on:

- How did implementation go? What worked? What can be improved?

- Were metrics met? What enabled this? What made it challenging?

- What can we learn from this piece of work?

- Shall we prolong the term of the decision as it is, or does it need changes?

In closing

A group decision making process can increase the quality of decisions, include more perspectives, and improve implementation and buy-in. It’s not always easy, but it will help your team grow!

Here are some of the key tips for improving collective decision making:

- Discuss decision making together, build a shared awareness and vocabulary;

- Write decisions on top of the meeting notes and make them available to everyone involved;

- Clarify when a decision has been taken vs when it’s still open for discussion;

- Give decisions an expiry date or “term”, then check and review them;

- Include metrics and expected results in the text of the decision to support such a review.

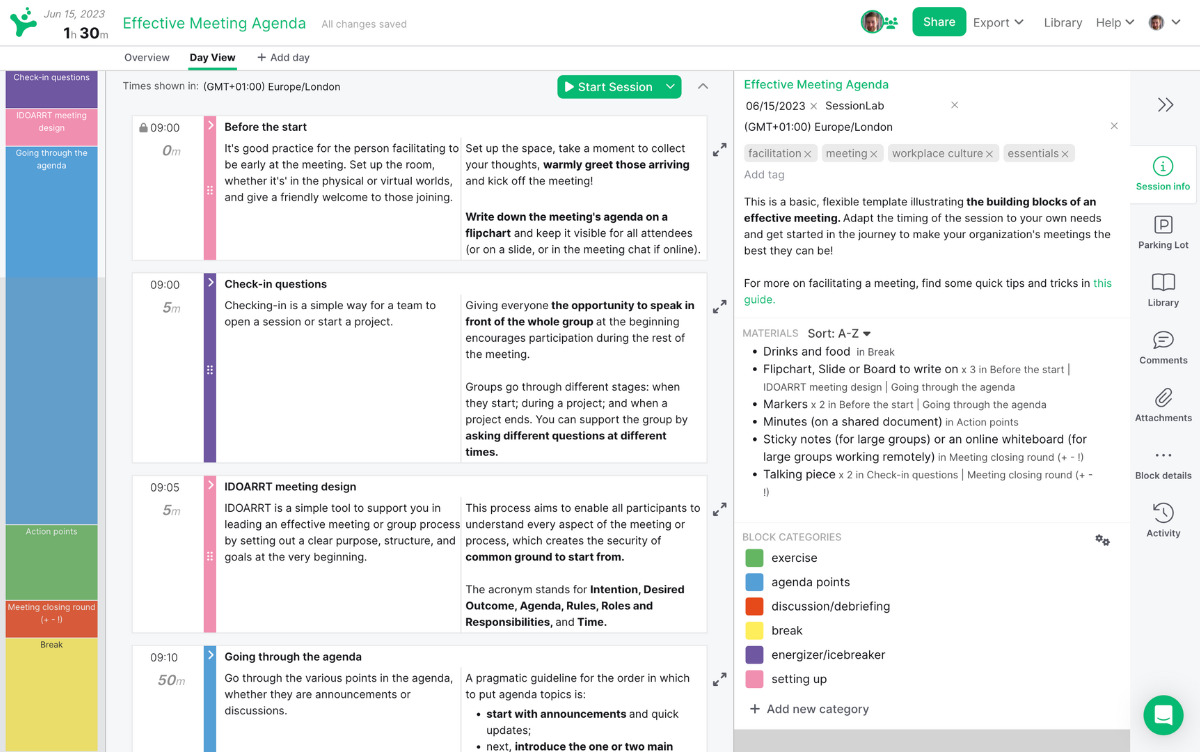

If you are looking to facilitate better decision-making in your groups and teams, check out these meeting templates for two examples of how decision-making works in a flow of activities:

- This template illustrates the case of a team consultation process to set goals for a quarter (and it’s the one we use at SessionLab!);

- Here you can find a workshop template for collective deliberation, detailing all the steps from brainstorming to deciding by consent.

Whether it’s the precious resource of our time and how to invest it in a project, or whether we are looking at larger collective problems (such as how to manage the distribution of water resources in a town or region), there are innumerable scenarios that call for effective group decision making.

A well-run, well-facilitated collective process can lead to better decisions, improving the way we work together and saving time, effort, and money in the long run.

Has this article helped you improve your practices? Do you have any application stories to share or further questions? Use the comments or join the conversation in our Community space!

Smart detailed advice. May I suggest that facilitators consider alternatives to dot-voting that better deter groupthink and bandwagon effect like using Feedback Frames.

https://www.sessionlab.com/methods/feedback-frames-for-prioritizing-a-brainstorm

Feedback Frames provide an efficient, reliable, fun and flexible technique for rating many ideas, with instant visual results. This simple in-person analog tool allows participants to secretly record their opinion of statements along a gradient of agreement by dropping tokens in a range of slots that are hidden by a cover. Results are later revealed as a visual graph of nuanced collective opinions for all to see.

The tool supports a collaborative consensus process while avoiding traditional sticker dot-voting problems such as the bandwagon effect, choice overload and vote-splitting.

What do you think?